Affording health care is a difficult issue for many Australians. And encouraging GPs to do more billing is one step the government is taking to ease the pressure.

So what would it take for doctors to pay more for everyone? About ours let’s read that this is possible and possible, according to the current standard of health.

But we show the current incentives for GPs to pay more aren’t enough to get us there.

Instead, we need to change health policies to increase coverage and make our health system sustainable.

How do bulk payment incentives work?

In recent years, the government has introduced various incentives to try to encourage (so patients pay nothing out of pocket).

Recently it has been “triple bulk-billing incentives” or “triple bonus” for short. These have been in place since November 2023.

Child abuse is a long-term investment, which can delay the onset of disease, and prevent generational poverty and health. Credit: Shutterstock

Under the incentives, GPs in urban areas are paid a bonus of $20.65 if they have multiple credit cards or children under 16. GPs in rural and remote areas are paid an extra $31.35-$39.65 . These bonus payments are in addition to the regular Medicare discounts that GPs receive.

But when we looked at whether these latest recommendations could work to boost crowdfunding, we found a split in the city-state.

The town doctors may not believe it

We’ve solved the triple bonus that won’t help most people in urban areas.

That’s because in these areas the bonus is much lower than what patients pay out of pocket. In other words, if doctors billed these groups more, their pay would be less than what they would have billed. So the bonus would not be enough of an incentive for them to pay more.

For example, we found in Greater Melbourne, the average out-of-pocket cost for a GP visit is the cheapest. $30-$56 depending on the city. This is significantly higher than the $20.65 triple bonus amount in urban areas. We see similar trends in all urban areas.

But the country’s doctors may be wavering

The picture is different in rural and remote areas. Here, the average out-of-pocket cost for an uncompensated GP visit varies widely – about $28-$52 in rural areas and $32-$123 in remote areas. The highest cost in the country was $79 but GP trips on Lord Howe Island were the most expensive, at $123.

For , motivation helps. In other words, it may be financially beneficial for GPs to pay more for these patients, but not where the out-of-pocket costs are higher than the bonus.

Our online map shows where GPs tend to charge the most bills. The map below shows how out-of-pocket costs vary around Australia.

How about multiple rates for everyone?

The picture is even more complicated when we start talking about bulk charging for GP visits – regardless of location or patient authorization card status.

We found that this would cost $950 million a year for all GP services, or $700 million a year for face-to-face GP consultations.

This can be achieved under the current budget, especially for face-to-face medical consultations.

The government has set aside $3.5 billion over five years for “triple bonus” incentives. That’s $700 million a year.

Can Medicare afford more universal coverage? We say ‘yes’, with caveats. Credit: Robyn Mackenzie/Shutterstock

We can, but should we?

Providing free GP visits for all would need careful consideration, as it would encourage more GP visits.

This can be a good thing, especially if people had previously skipped good care because of high costs. However, it may encourage more people to see their GP unnecessarily, taking limited resources away from those who really need them. This can increase the waiting time for everyone.

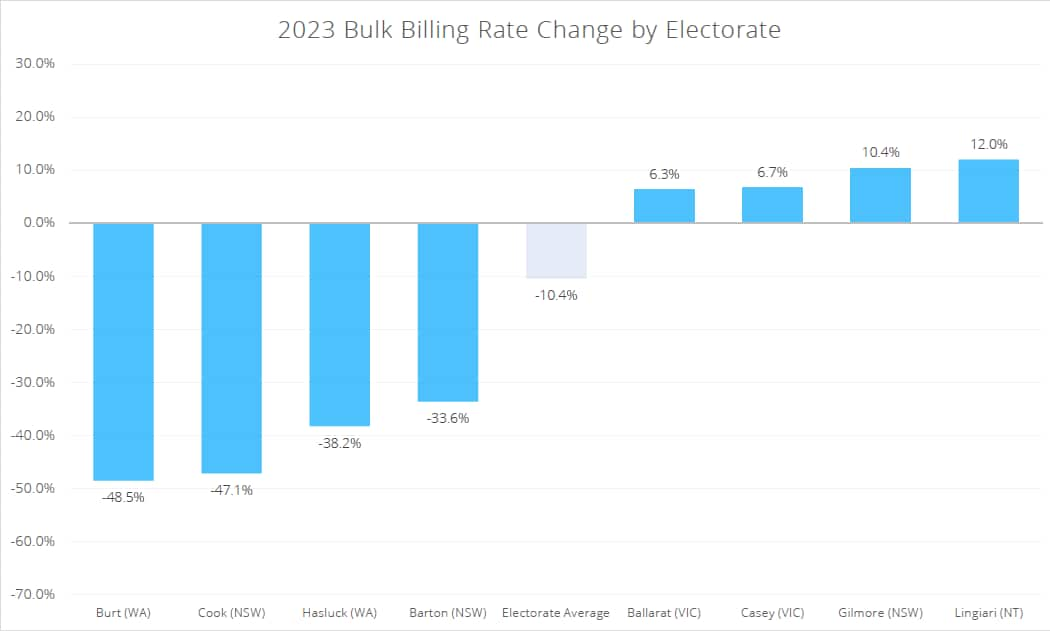

Dividend – 2023 Bulk Payment Rate Change. Credit: Cleanbill, A Dividend Report.

So providing free GP visits for all may not be efficient or sustainable, even within the budget.

But paying more than $50 for a GP visit, as many do, seems too expensive and inefficient for the health system.

That’s because primary care is often considered high quality and preventive care. So, if people can’t go to the doctor, this can lead to higher hospital and emergency room costs.

So we need to balance it out to make primary care easier and stable.

How can we have balance?

One, concession card holders with children should receive free primary care regardless of where they live. This will allow balanced care for people who need the most health care. Child abuse is a long-term investment, which can delay the onset of diseases, and prevent generational poverty and health.

Second, the government can also provide free primary care to all people in rural and remote areas. It could do this by dropping the triple bonus to match what GPs currently charge. Over time, doctors and the government can evaluate and negotiate the right prices for doctors to charge. This can be adjusted for inflation and other measures.

Third, the government could increase Medicare rebates (the amount Medicare pays a doctor for a GP visit) so uninsured patients only pay $20-$30 per visit. We consider this to be an affordable cost that will not result in more primary care spending than necessary.

Fourth, the government could develop a policy to reduce unnecessary GP visits that take up less GP time for patients in high need. For example, patients currently need to see doctors to get referrals even though they already have an established specialist for their ongoing chronic conditions.

Fifth, the government can provide the necessary funding for GPs to improve patient outcomes and reward doctors who provide high-quality preventive care. The current fee-for-service system hurts good doctors who keep their patients healthy because doctors don’t get paid if their patients don’t come back.

Yuting Zhang is a professor of health economics at the University of Melbourne.

Karinna Saxby is a researcher at the Melbourne Center at the University of Melbourne.